The continuing popularity of the dahlia

is not surprising. Dahlias come in an amazing variety of colours,

shapes and sizes. This member of the Aster family, (Asteraceae), reproduces

vegetatively. Onions, hyacinths, and tulips produce bulbs, crocuses produce a bulb-like

structure called a corm, but

dahlias (and potatoes) produce tubers.

Dahlias are named after the Swedish

18th century botanist Anders

Dahl. Sixteenth century Spanish conquistadors came upon

the ancestors of modern dahlias while conquering the Aztecs in the

mountains of Mexico and Guatemala. (All thirty-five species of

the genus Dahlia are found in

this relatively small region.) Several hundred years later, seeds

and tubers were located at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Madrid,

Spain, from which they were distributed throughout western

Europe. Since then, plant breeders have been actively breeding

dahlias to produce thousands of hybrids. The tremendous variety

of these cultivars is due to the fact that most plants have two sets of

homologous chromosomes, whereas dahlias have eight sets! Dahlias

are therefore referred to as octoploids.

Several dahlia hybrids are

investigated in this article, however photomicrographs of a flower’s

reproductive structures are shown only for the last hybrid (near the

end of the article).

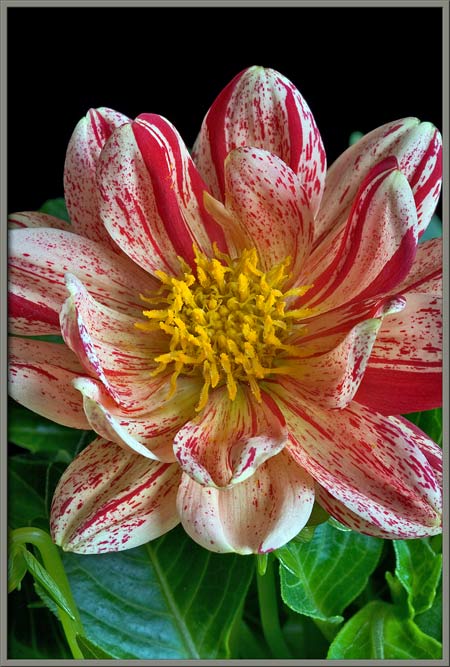

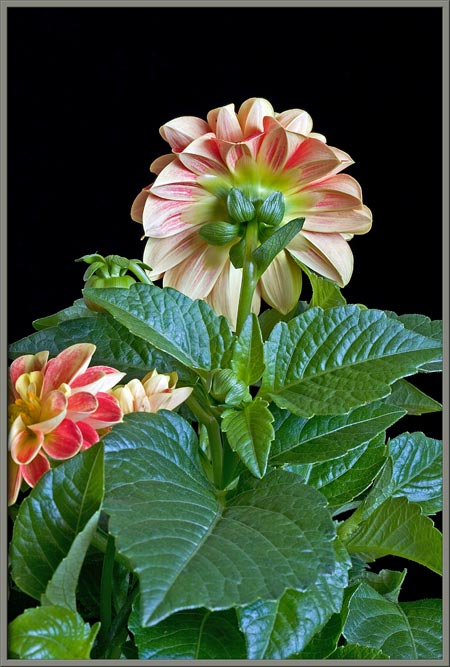

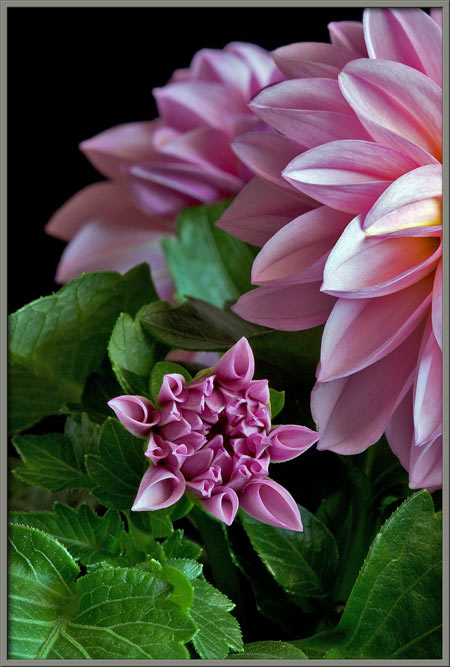

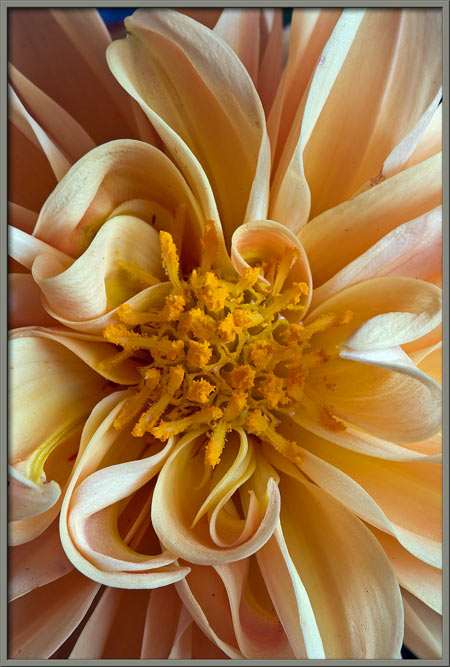

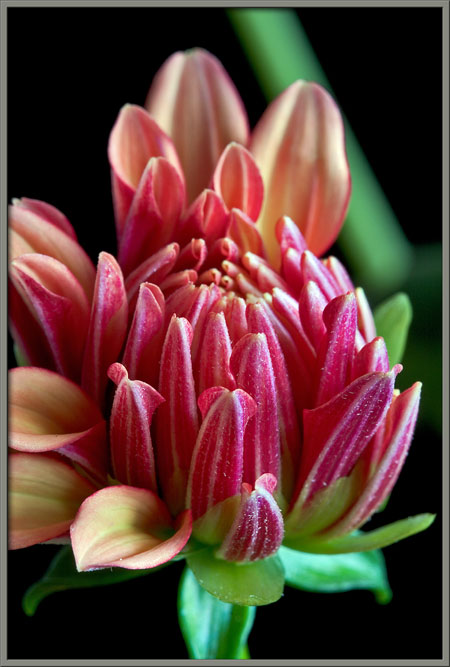

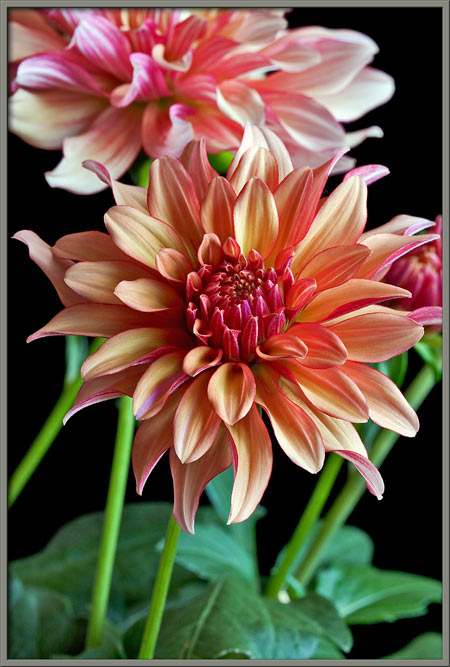

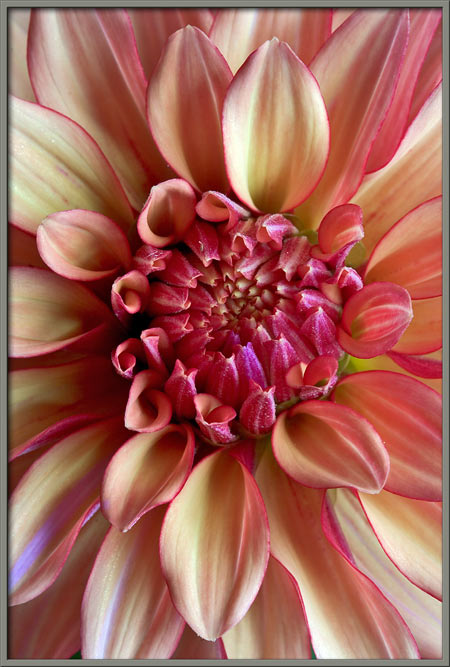

Dahlia

hortensis ‘Patricia’

The first image in the article

shows this spectacularly coloured cultivar. Notice in the image

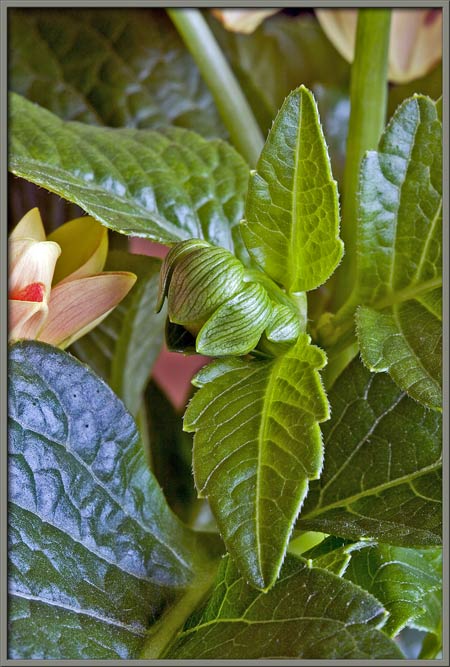

below that a dahlia bud is ringed by five oval, bright green

leaflets. It’s hard to believe that the flower shown in the image

on the right had such an unspectacular origin.

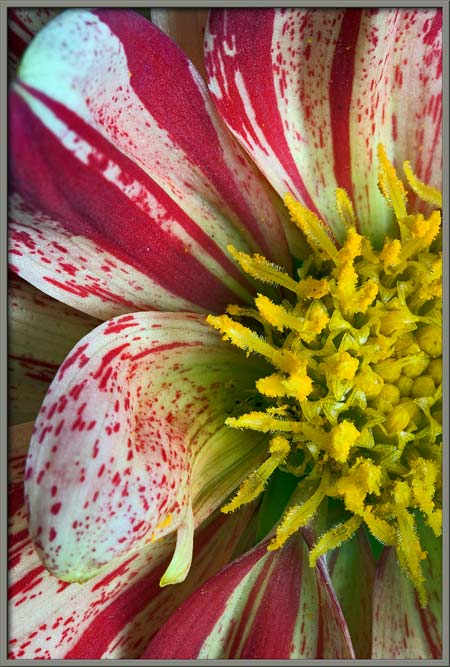

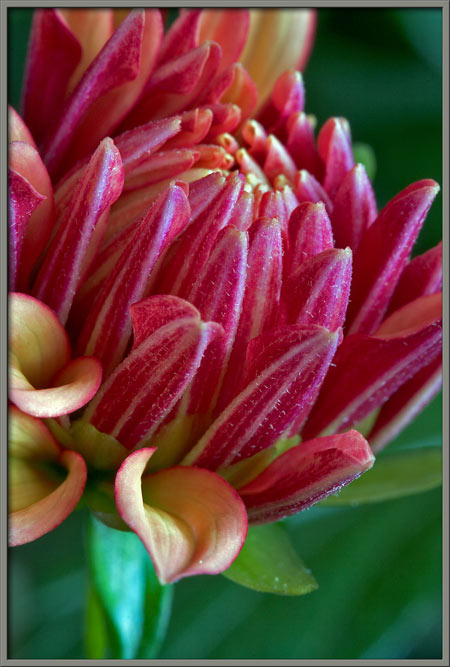

Closer views of the centre of a

flower show many columnar, pollen encrusted pistils emerging from the

disk flowers of the bloom. Careful inspection of the right-hand

image reveals the five pointed, star-like shape made by the fused

petals of each disk flower.

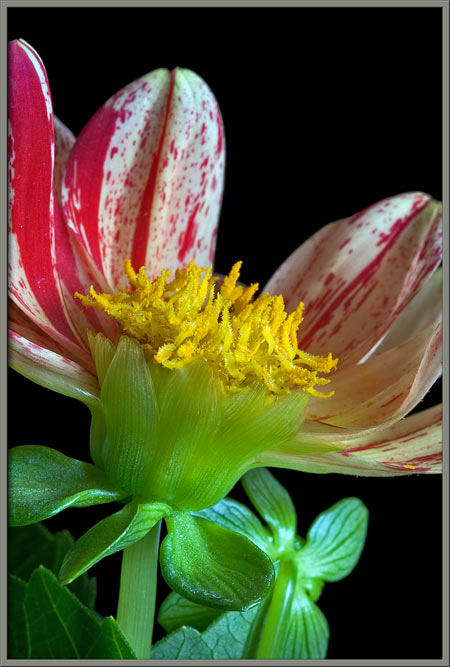

Several petals (better called ray

flowers) have been removed to better show the yellow forest of pistils

(stigmas and styles) at the centre of a flowerhead. A bloom is

cupped by a ring of light green sepals (modified leaves) that make up

the flower’s involucre.

The two images that follow show the

bi-lobed stigmas of disk flowers. Notice the fringe of hair-like

protuberances on each lobe.

I must confess that I do not have a

“green thumb”. Many times, after photographing a flower, I have

attempted to keep the plant alive for a protracted period of

time. Usually the attempt is unsuccessful! In this case,

flowers continued to bloom, but they were smaller, and much less

spectacular than the original blooms. Here is an example of a

“second generation” flower to prove my point.

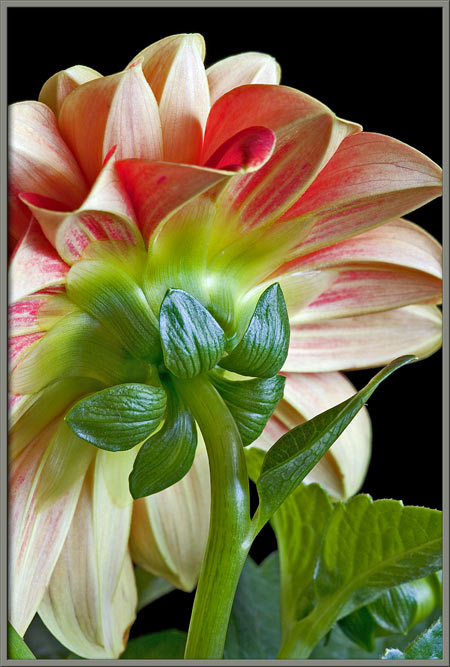

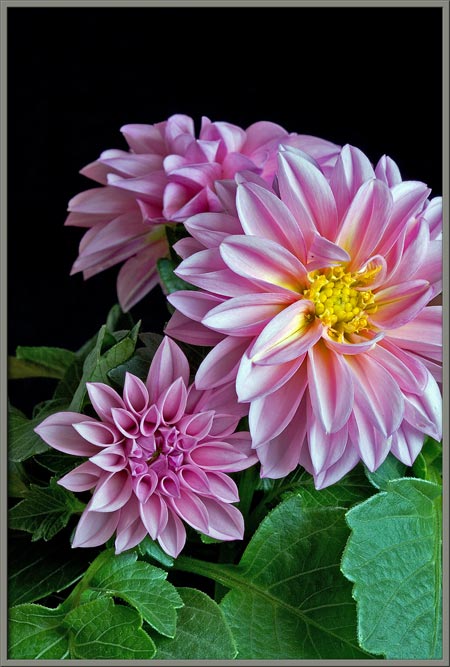

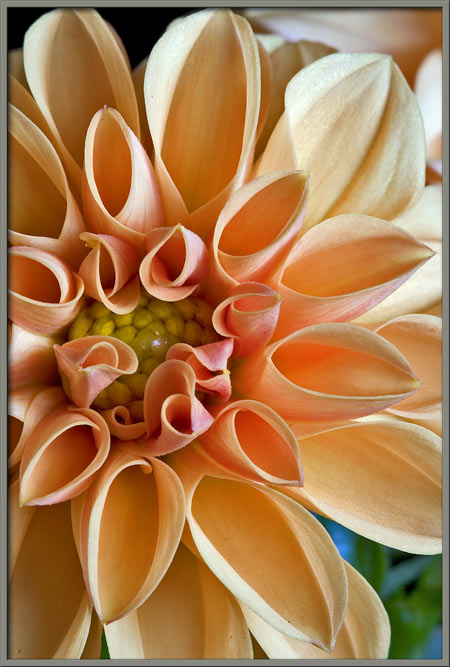

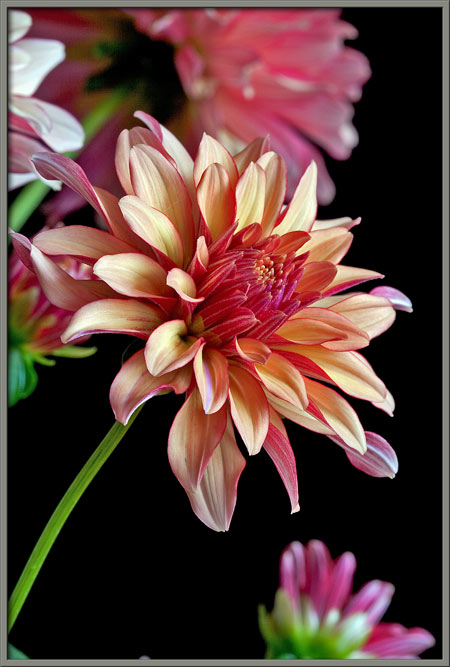

Dahlia

hortensis ‘Apricot Sunrise’

This second cultivar has a less

complicated petal decoration. Notice how the innermost petals

have a rolled-into-a-tube appearance. Also note that the bud

shown in the image on the right has two small leaflets beneath it, as

well as a ring of striated smaller leaflets at its base.

A short time later, the leaflets

have separated from the pumpkin-shaped bud.

If a blooming flower is viewed from

behind, the ring of leaflets, and a second ring of larger, paler green

sepals (closest to the petals) can be seen clearly.

When the flowerhead first blooms,

it is the outer ray flowers that predominate. A dome of

yet-to-bloom disk flowers can be seen at the centre of the flowerhead.

Somewhat later, the ray flowers

have ‘opened up’ to reveal the central disk flowers with their

projecting, pollen covered pistils.

The higher magnification view below

shows that not all of the disk flowers have bloomed.

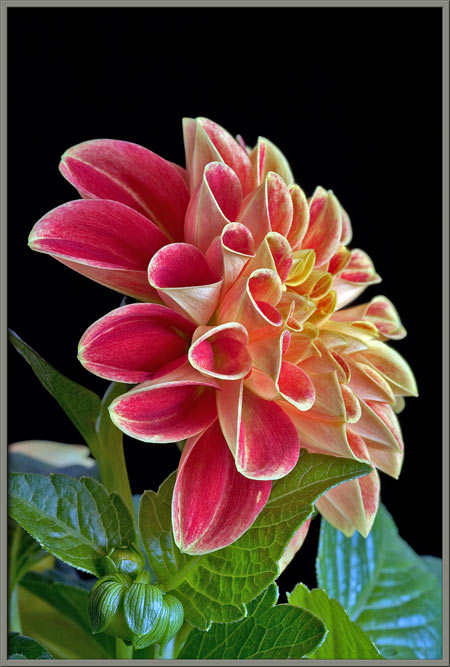

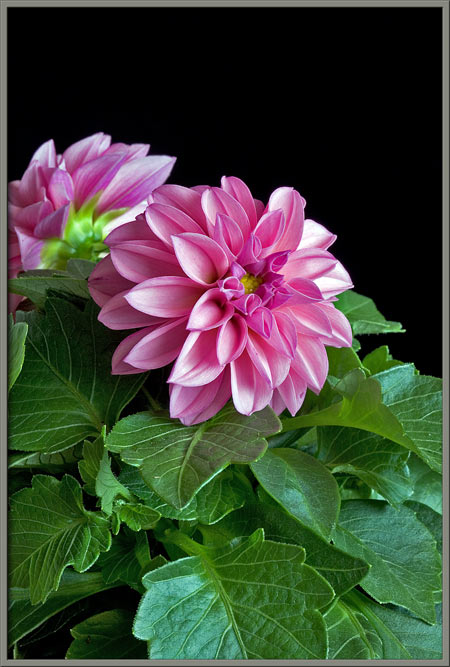

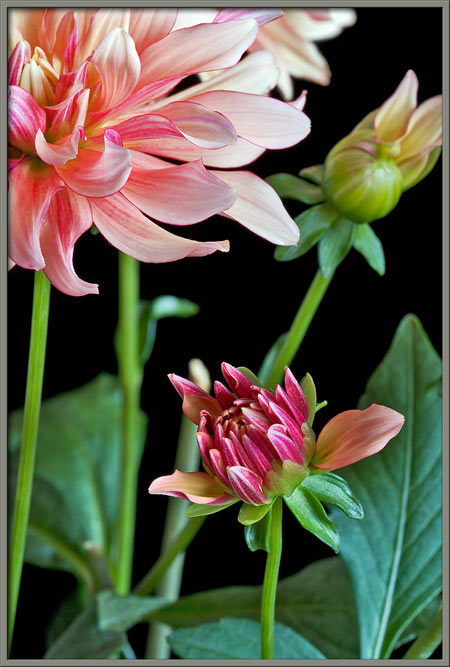

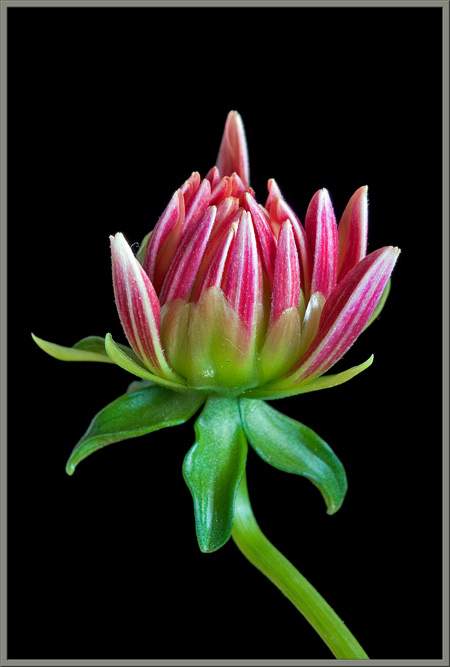

Dahlia hortensis ‘Emily’

This third hybrid has solid pink

colouration. The bloom has just opened, and it too has ray

flowers with petals that are curled into tubes near the central

disk. Notice in the image at right, that none of the disk flowers

have opened.

Notice the striking contrast

between the opening bud at left and the blooming one at right.

The same strangely angular bud is

shown twelve hours later in the image on the right below.

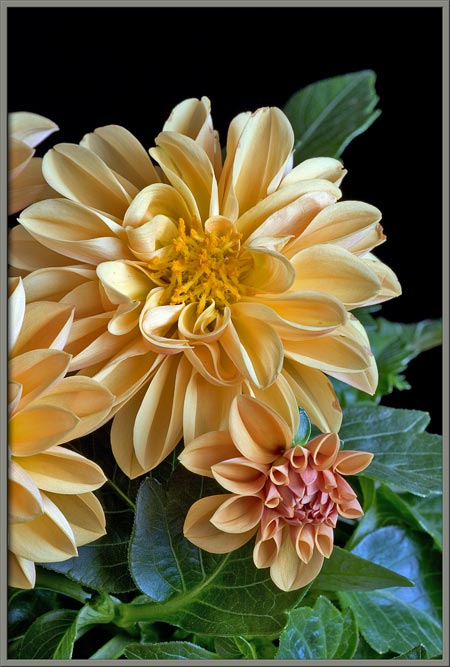

Dahlia

hortensis ‘Linda’

Here is another hybrid, this time

with a solid yellow-orange colouration. Early stage blooms tend

to be more orange than yellow (far right). The bloom in the

centre has the outermost disk flowers open, while the one on the left

is almost mature.

Notice the change in appearance of

the bud as it grows. Unopened yellow disk flowers are just

visible at the centre of the bud in the image at right.

As the ray flowers bend away from

the centre, the central disk flowers, in bud stage, become visible

. It appears that they are all temporarily covered by a thin

transparent membrane. In the image at right, if you look closely,

you can see that some of the outer disk flowers have bloomed, and the

pollen coated stigmas extend out from the distorted fused petal

assemblies.

A mature dahlia flower of this

hybrid can be seen below. Several dozen stigmas extend an

appreciable distance out of the disk flowers.

If you look just below centre in

the right-hand image, you can see one of the disk flowers with its five

tiny, pointed, yellow petals fused together. Also note the very

stocky style supporting an elongated, orange stigma coated with pollen.

Dahlia

hortensis ‘Unknown’

Unfortunately, the supplier of this

dahlia hybrid neglected to insert the usual identification tags into

the pots. I have been unable to identify it.

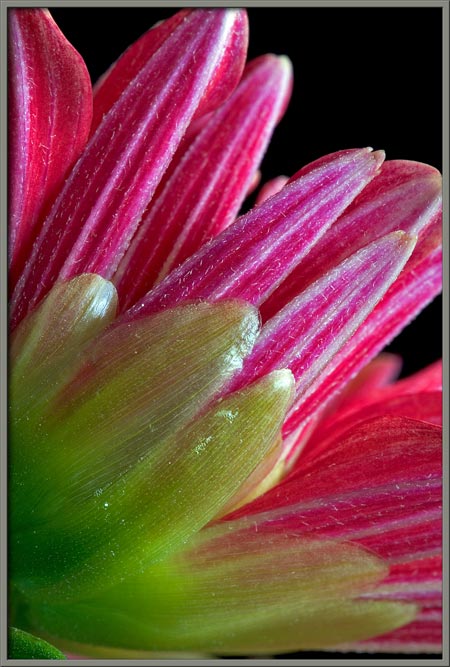

Strangely,

this cultivar has ray flower petals with a solid pinkish-beige colour

on the upper surface, and brilliant red and white longitudinal stripes

on the under surface. In addition, even when a bloom is

completely mature, it displays no disk flowers.

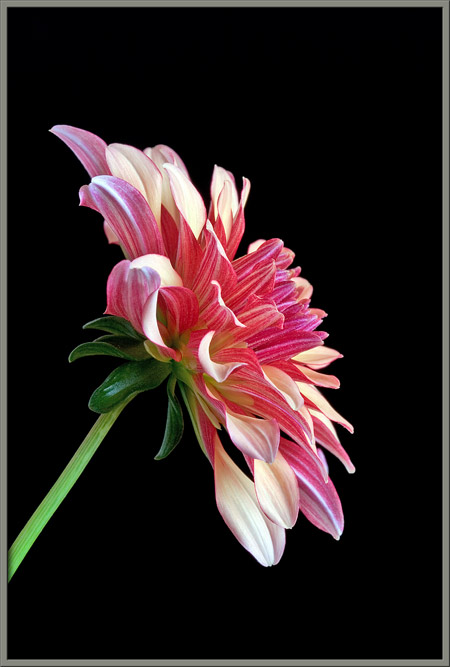

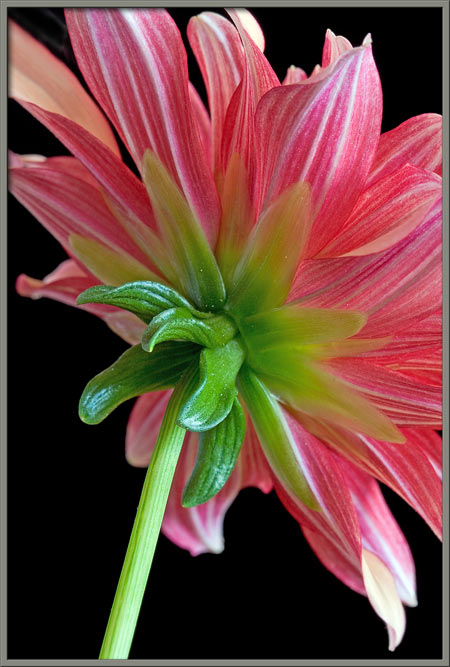

The striped under-surfaces can be

seen perfectly in the opening bud. Here again, there is a lower

ring of five, bright green leaflets, and another ring of lighter green

sepals beneath the outer ray flowers.

An hour later, the ray flowers have

begun to open out towards their final positions.

Notice the extreme contrast between

the upper, and what will eventually be the lower surfaces of ray flower

petals.

The pale, translucent, green sepals

are in contact with the ray flower petals at this stage. Notice

the fine, white, longitudinal striations on each of the sepals.

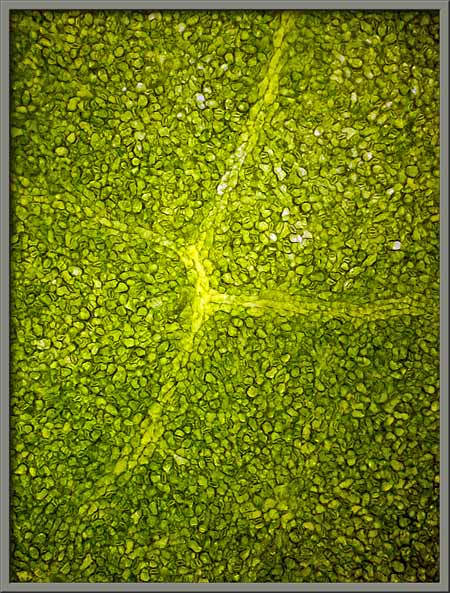

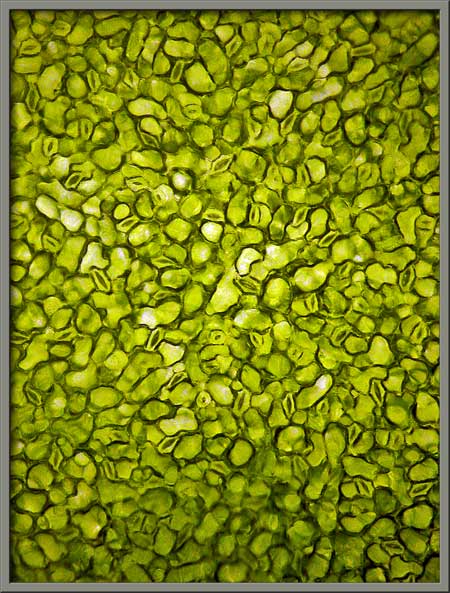

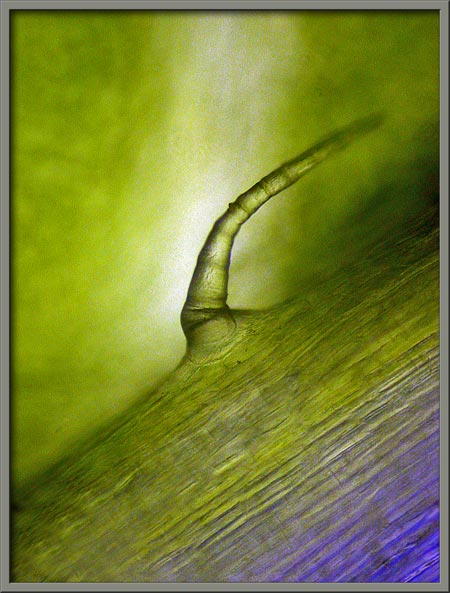

If one of these sepals is examined

under the microscope, the oval stoma

and guard cells that regulate

gas entry into and out of the sepal can be seen.

Here are front and side views of an

almost mature bloom.

Why look at the back-side of a

flower? In the case of this hybrid, the back is the “best side”!

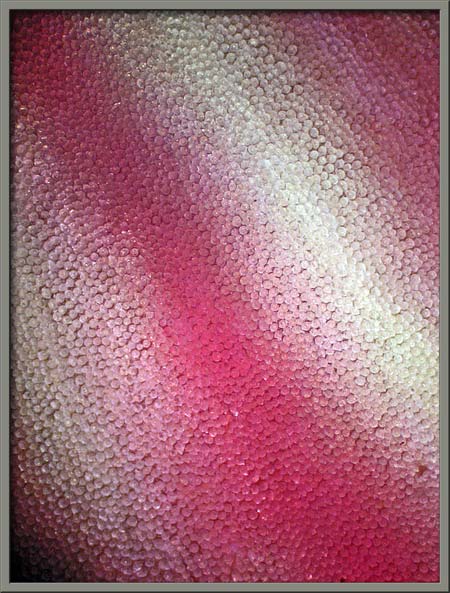

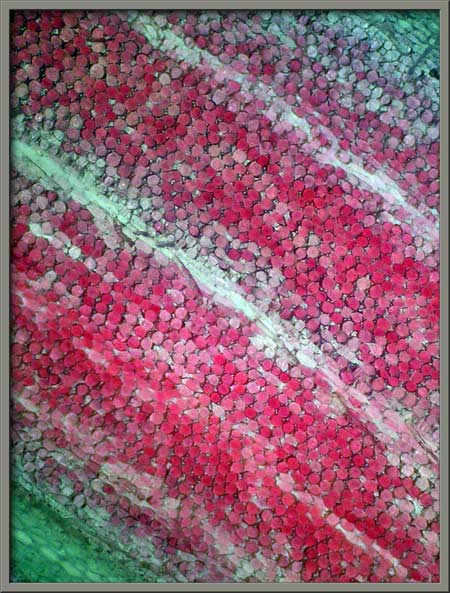

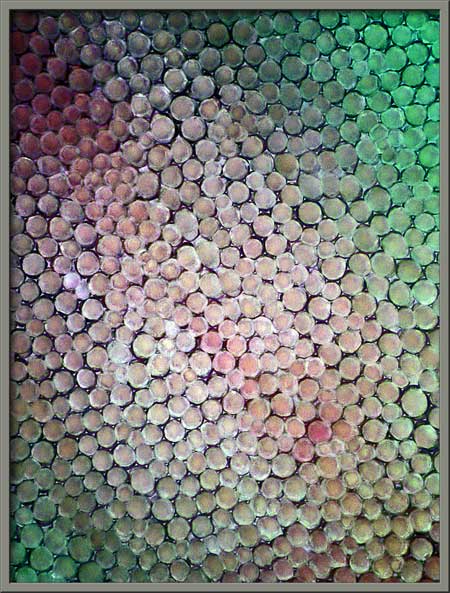

A low magnification photomicrograph

of the underside of a ray flower petal can be seen on the right below.

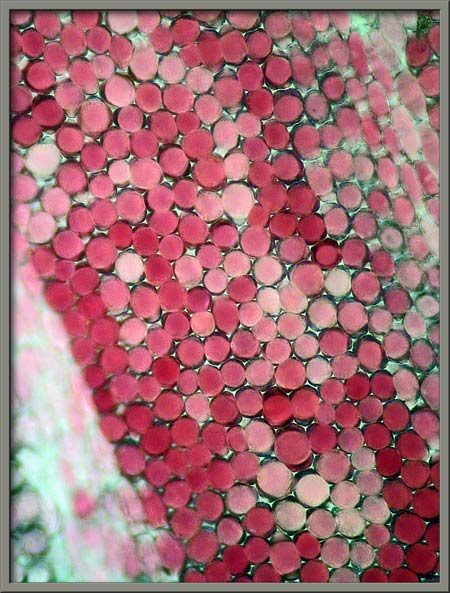

Higher magnifications reveal the

almost spherical cells that form the surface layer of a petal.

Note that the three images have had Photoshop’s

“auto-levels” applied in order

to increase contrast. The images are thus not true-colour.

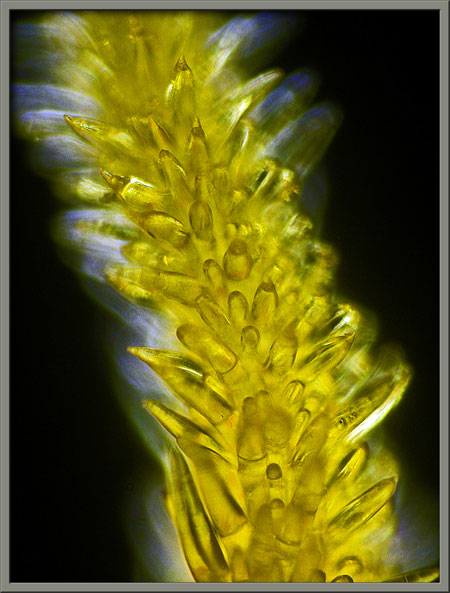

The two photomicrographs below show

a typical dahlia disk flower. Notice the five, pointed petals,

that are fused together below their tips. The first image reveals

the style protruding out from the ring of petals. Where

are the stamens with their anthers, and supporting filaments?

They never protrude far enough out of the disk flower to be visible to

an observer. If you are sharp-eyed however, you can just make out

a darker shadow behind each petal, (the anther), and a number of

particles surrounding each shadow, (the pollen grains). As the

stigma is pushed out of the petal tube by the style, it comes into

contact with the anthers, and copious amounts of pollen become stuck to

its many hair-like protuberances. Self-pollination is discouraged

(but not entirely prevented), by having the stigma become receptive

only after its passage through its own ring of anthers.

A complete graphical index of all of my flower articles can be found here.

The Colourful World of Chemical Crystals

A complete graphical index

of all of my crystal articles can be found here.